Peggy Noonan recently wrote, “The biggest political change in my lifetime is that Americans no longer assume that their children will have it better than they did. This is a huge break with the past, with assumptions and traditions that shaped us” (The Wall Street Journal ; August 7, 2010). We can probably surmise that sometime during the Great Depression, Americans experienced a similar sentiment, worrying—or even being convinced—that America’s long-term capacity for wealth creation was drawing to an end. The growing concerns about America’s economy are not unfounded.

Wealth creation and the hope for its future in the United States can largely be measured through the total return of the stock market (including dividends), after taking into account the impact of inflation. Dividends must be included and inflation’s impact must be removed in order to track the purchasing power of a dollar invested in stocks. Purchasing power is a concept we all understand. It also means much more than whether the price of one’s stocks went up or down. Thus, this analysis will answer the question, “How much can I buy with the proceeds from my investments?”

When we compare the performance of our most recent decade (the Great Recession) with that of the Great Depression, there is a much stronger correlation than we could ever have imagined. In the above chart, we first note that the highest peak came in March 2000, which was the end of the bull market that began in 1982. Since then, new highs have never been reached. Shockingly, equity investors of the Great Recession are worse off than they were at this point in time during the Great Depression. Now, 125 months after the market peak in March 2000, equity investors have only 70 cents remaining, versus 85 cents for those suffering through the Great Depression. This fact helps to explain why, even without the bread lines of the 1930’s, Americans know that something is terribly wrong. We have been slow to create wealth for a long time. The future feels bleak.

During the Great Depression, 125 months after the market peak of September 1929 it was January of 1940. World War II had begun the prior year in August, and later in the year would come the Battle of Britain and the November re-election of Franklin D. Roosevelt for his third term. Today, the United States is at war. We also have a forthcoming mid-term election. It could set the stage for reducing some of the uncertainty that has so spooked investors. Hopefully, the pattern on the chart will diverge from history and avoid a decline like the one from early-1940 to mid-1942. As always, the future remains uncertain.

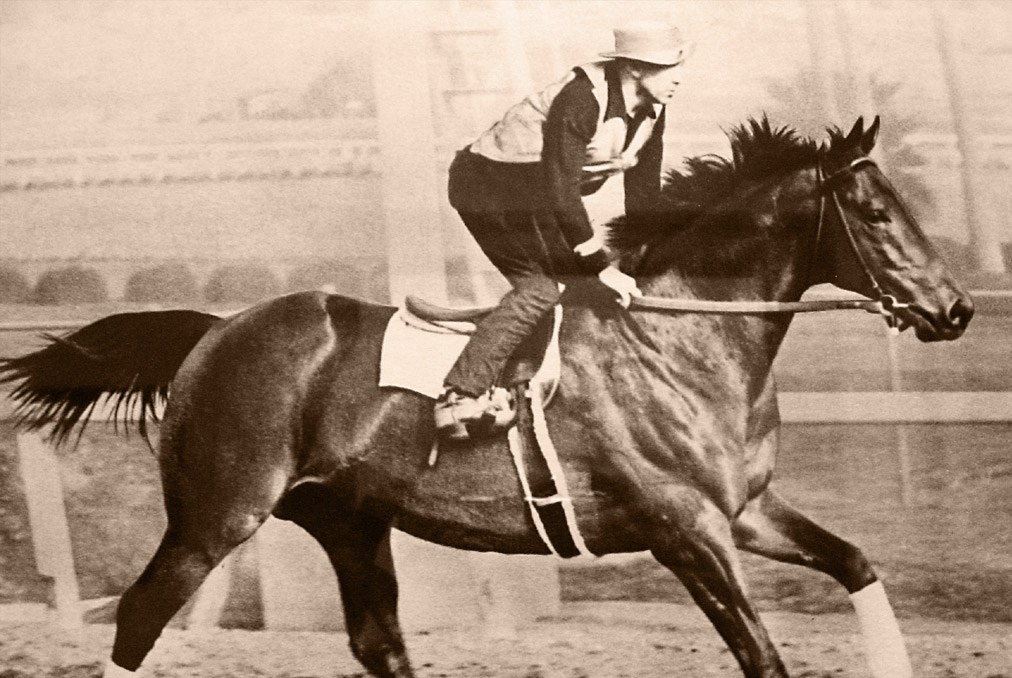

After an inauspicious start in the mid-1930’s, a racehorse named Seabiscuit became an unlikely champion and a symbol of hope for many Americans during the Great Depression. He was undersized, knobby-kneed, and given to sleeping and eating for long periods. After defeating War Admiral in “The Match of the Century” and being named “Horse of the Year” in 1938, Seabiscuit ruptured a ligament in his front left leg in 1939. Many predicted he would never race again. Nurtured back to health by his owners, Seabiscuit recovered by the spring of 1940 and was allowed to race, winning several firsts before retiring later that year.

After America’s inauspicious start hundreds of years ago, one hallmark has been its ability to create wealth. We refuse to believe that America’s Seabiscuit economy of the last two centuries is ready for early retirement. The credit crisis was a terrible accident, but with even the mildest support (and some time), the economy will heal naturally. Note to the politicians and parties: Quit redesigning the racetrack, just maintain it. Remember that the “American Dream” comes with a bootstrap, not a free ticket to the box seats. Put the fiscal house in order or the only people left in the stands will be your weary creditors. And then, please, Mr. Washington: let the reins out.

Charles W. Robinson III, CFA

Chief Investment Officer